A new joint venture between Americas Gold and Silver (USAS) and United States Antimony (UAMY) is targeting the weak link in the U.S. antimony chain, processing and finishing. The plan is to build and operate an antimony processing facility in Idaho’s Silver Valley, tied directly to Americas’ Galena Complex, so material produced in Idaho can be converted into finished antimony products inside the United States, instead of being routed into overseas refining systems.

This is not a “new deposit” story. It is a supply-chain control story, the kind of project that changes who controls lead times, product form, and final delivery reliability, even if the mine has been producing for years.

The bottleneck was never the rock

Galena is already producing antimony. In 2025, Americas reported 561,000 pounds of antimony contained in concentrate from the Galena Complex. That detail matters because it clarifies the real issue. The U.S. does not start from zero on upstream supply, there is already domestic feed.

The friction starts after the concentrate exists. Concentrate is an intermediate product, it is not a standardized finished material that downstream buyers can just slot into manufacturing plans. It still has to move through conversion steps that turn a variable, impurity-bearing feed into defined forms, consistent chemistry, documented lots, and repeatable delivery schedules. That conversion stage is where constraints get imposed, and where leverage usually lives.

When domestic conversion capacity is thin, the value-add tends to migrate out of the country with the concentrate. The plant that takes the feed controls the queue, sets the commercial terms, determines payability and penalties, and decides when a run happens. Even if your mine is producing steadily, you can still end up operating on someone else’s schedule if the conversion node is external. From a security perspective, that is where exposure accumulates, not at the extraction step.

That is the gap this JV is designed to close, it aims to move the chain from “we can produce concentrate” to “we can make finished output domestically,” with a more direct line between mine feed and usable product.

What the JV actually does, and why the structure matters

The joint venture splits ownership 51% to Americas and 49% to U.S. Antimony, which is a simple way of signaling that this is meant to be a long-term operating asset, not a short-term tolling arrangement. Governance is handled through a six-member management committee, split evenly, with U.S. Antimony serving as the operator. In practice, that kind of structure is trying to balance two things at once, keep the asset tied to the mine’s production profile, while also putting day-to-day plant execution in the hands of a company that already lives in the processing and marketing world.

On inputs and site, the design is straightforward. Americas contributes the Galena site under existing operating permits and supplies antimony feed to the JV on market terms. Over time, the facility may also be able to process feed from other sources, which is the difference between a “single-mine add-on” and a broader domestic processing node. If the plant can accept third-party material later, it has a path to becoming more than just a captive outlet, it can become part of the wider domestic supply backbone.

Commercially, U.S. Antimony’s role is not only plant operation, it is also downstream access. The company brings processing experience and a marketing network that includes government channels, and, subject to follow-on supply agreements, it would purchase the JV’s antimony output on market terms. That last phrase sounds bland, but it is doing work. “Market terms” implies the pricing and offtake framework is meant to be defensible and repeatable, not a one-off sweetheart deal that only works in one price environment.

The timeline language contemplates an 18-month build period, starting after an agreed project budget is completed. That is important because it anchors expectations. This is not a vague “someday” project, but it is also not a next-quarter switch flip. The sequencing will matter, budget, permitting, construction, commissioning, then qualification.

Why processing is the control point

A domestic mine feedstock is valuable, but it is not the same thing as domestic control over finished material. The choke point in specialty metals is often not extraction, it is the conversion step where material becomes usable, spec’d, and deliverable at scale.

Processing is where you can get squeezed in ways that have nothing to do with geology:

Third-party capacity limits can put you in a queue behind other feeds. Toll terms can shift with market tightness. Export controls and compliance friction can add delays or force rerouting. “Friendly” processing relationships can still leave you with long logistics chains, and long chains mean more failure modes. Even in normal conditions, selling concentrate tends to push you into a different economic lane than selling finished product, the processor captures a larger share of the value-add because they control the transformation.

There is also the less discussed part, qualification and repeatability. Manufacturing systems, especially defense-adjacent ones, care about consistent lots, documented chemistry, and predictable deliveries. If conversion happens outside the domestic chain, the feedback loop between end user requirements and upstream production can get slower and messier. A domestic conversion node shortens that loop, even if the mine output stays the same.

The JV’s pitch is basically, “mine to finished product” within a domestic loop. That is not glamorous. It is functional. It turns upstream production into something that procurement, planning, and manufacturing can actually schedule around.

Antimony use is broad, and that is why continuity matters

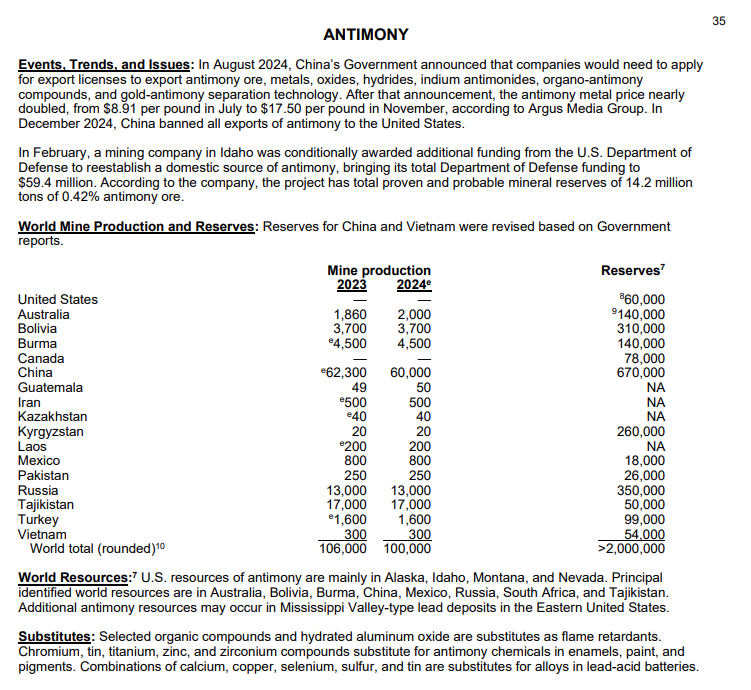

Antimony’s biggest end uses are not mysterious. The USGS notes antimony metal is widely used as a hardener in lead, and antimony trioxide is widely used in flame-retardant formulations, including applications tied to transportation and aviation interiors. Those categories are a good reminder of how these materials behave in the real economy. Antimony is not a single-product niche, it is embedded across systems that require compliance, consistency, and repeat supply.

That embedded nature is why conversion capacity matters so much. When a material shows up across many product families, demand can shift quickly, and the stress usually concentrates at the processing stage. Mines cannot instantly change throughput. Conversion plants also cannot instantly add furnace time. When the overall system tightens, the player that controls processing slots often controls who gets material first, and who gets pushed to the back of the line.

So the practical question becomes less “do we have ore” and more “can we reliably produce finished output in the form customers need, at the cadence they need, without an external gatekeeper.”

Defense production is ramping, and inputs get less forgiving

The timing here lines up with a broader defense-industrial push toward higher output and longer-run planning. On February 4, 2026, Reuters reported that Raytheon (RTX) reached a multi-year framework with the Pentagon to lift production capacity for several major munitions, including targets such as Tomahawk output rising from roughly 60 per year toward 1,000 annually, AMRAAM to at least 1,900 per year, and SM-6 to over 500 per year from about 125. RTX’s own release mirrors those scale targets.

When programs move into that kind of sustained higher throughput, the system’s tolerance for bottlenecks drops. Anything that forces long lead times, unpredictable deliveries, or external dependencies becomes more consequential. You do not need antimony to be the headline material in a missile program for it to matter. If a specialty metal, or a derived product form, becomes inconsistent or delayed, it shows up downstream as schedule risk, requalification headaches, substitution efforts, or procurement scrambling.

That is why “processing inside the U.S.” is a meaningful sentence in this context. It is about tightening the supply chain so scaling production does not amplify vulnerabilities that were tolerable at lower volume.

What changes if this works, and what stays the same

This project does not rewrite U.S. mineral reserves. It changes where control and value are captured.

If the mine-to-finished pathway becomes real and repeatable, a few things shift:

First, more margin can stay onshore because conversion economics are not automatically ceded to external processors. Second, schedule exposure can decrease because the conversion step is closer to the feed source and run by a JV aligned around the same supply goal. Third, end users can get a tighter loop for ordering, qualification, and repeat supply. Even modest gains in predictability can matter in procurement environments that plan in lots, months, and program-year cycles.

It also functions as a template for how industrial resilience is getting built right now. Instead of waiting for a single firm to build an entire chain alone, you see more “stacked” partnerships, miners linking up with processors and downstream networks to create continuity. That approach spreads execution risk, reduces time to capability, and makes it easier to connect upstream production to real end markets.

The structural shift is not that the U.S. suddenly has more antimony in the ground. The shift is that the U.S. can increase the share of the chain it can run domestically, on a domestic schedule, with domestic accountability.

What to watch next

The next phase is where projects like this either become operational capability or stay as a press-release outline.

Watch the project budget and sequencing, because the 18-month clock starts after the agreed budget is in place. Watch construction permitting and execution, since even with existing operating permits, a new facility still has to clear approvals and build milestones. Watch the purchase and supply agreements behind the “market terms” language, because those details determine whether the output has a stable home and predictable commercial flow.

Also watch product form and qualification, what “finished material” means in practice, and how quickly customers can qualify it for specific applications. Finally, watch whether the facility can take third-party feed over time. That is how this becomes a broader domestic processing node rather than a single-mine solution, and that is where the strategic value tends to compound.

If all of that lines up, the story stays the same at the surface, Galena produces concentrate, but the function changes underneath. Finished antimony output becomes a domestic product, with fewer external gates between extraction and end use. That is the kind of change that does not always grab headlines, but it does change how the supply chain behaves when pressure rises.