For centuries, silver’s primary role was monetary – coinage and bullion hoards – with relatively few industrial uses. That changed dramatically by the early 20th century. The advent of photography introduced a new, voracious demand for silver in the form of light-sensitive silver halide chemicals. By the time of the First World War (1914–1918), this once “useless” precious metal (beyond money or decoration) had become a strategic industrial resource. Governments and industries were diverting silver from vaults and mints into film and photographic plates, effectively transitioning silver from currency to a crucial commodity.

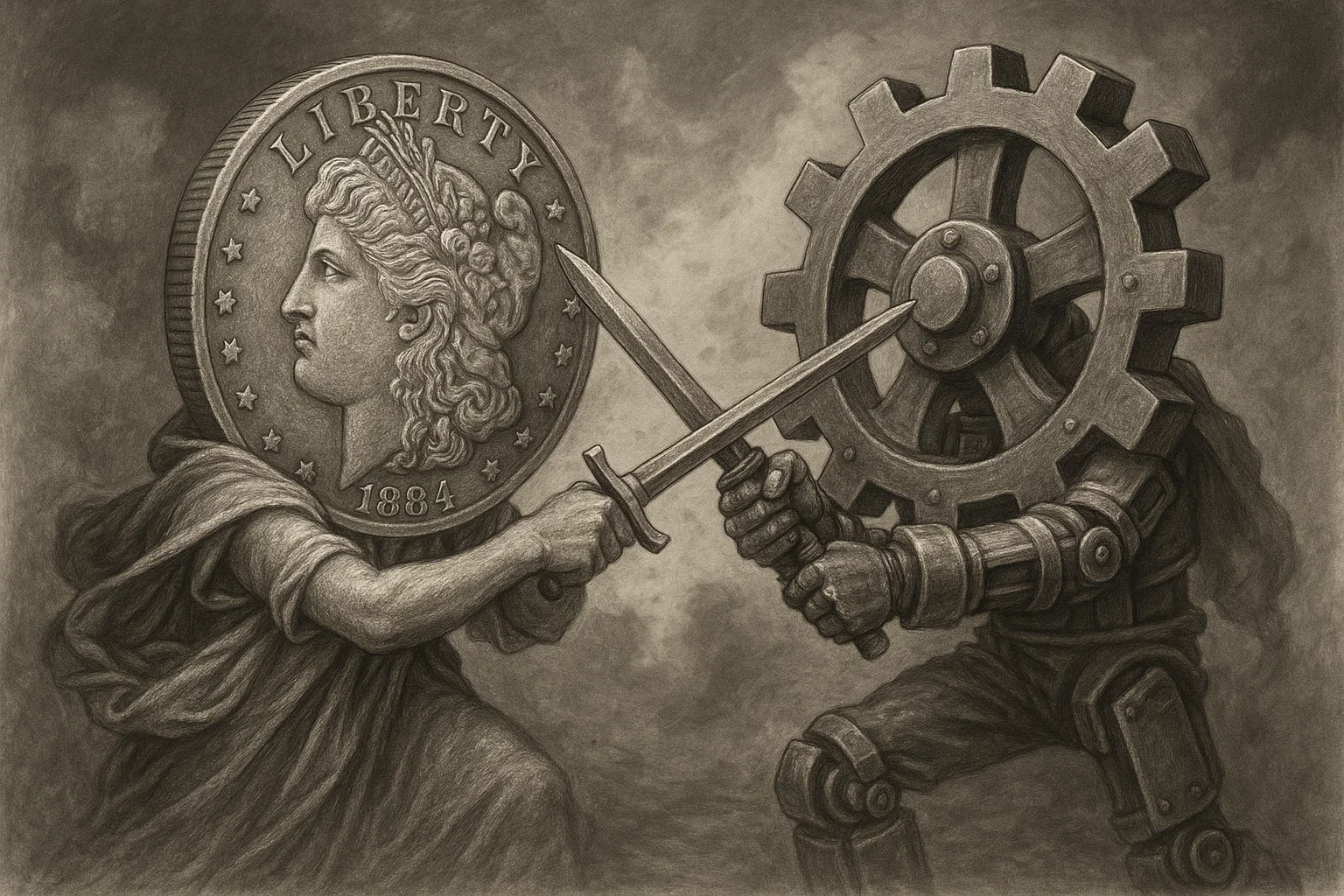

We reviewed the U.S. Bureau of Mines silver statistics from the World War I era and examines how military and civilian photography during the war consumed massive quantities of silver. We will see that photography – the high-tech innovation of its day – became one of the first widespread industrial sinks for silver, permanently removing millions of ounces from monetary circulation. The analysis spans all major combatant nations and considers espionage and reconnaissance uses of photography in the lead-up to and during WWI. In doing so, we gain insight into how war-driven industrial demand for silver set the stage for modern supply pressures – a silver war between monetary tradition and industrial necessity that continues to this day.

War-Era Silver Production and Demand

- World production dipped sharply in 1914 as revolution in Mexico and the outbreak of hostilities disrupted mines, falling from a 1911–13 peak of ≈227 million oz to 177.25 million oz in 1914, then recovering to 189.45 million oz in 1915, before oscillating between 174.63 million oz (1916) and 203.43 million oz (1918) .

- U.S. production followed a different arc: after peaking at 75 million oz in 1915, it fell to ≈67 million oz by 1918 due to wartime inflation of base-metal by-products

– and wartime demand helped keep production strong. Yet unlike in earlier decades, when most silver would have gone into coins or treasury reserves, a growing share in the 1910s was siphoned off for industrial uses like photography.

Major Silver Demands During WWI:

- Military Photography: Aerial reconnaissance and battlefield photography (discussed in detail below) consumed silver in the form of photographic plates and film.

- Medical X-Rays: The militaries used X-ray imaging (a silver-based film technology) to treat wounded soldiers, another new demand on silver.

- Civilian Photography: Amateur and press photographers continued to use silver-loaded film throughout the war, albeit with some wartime restrictions.

- Coinage and Finance: Silver was still needed for coinage (especially in British India’s currency) and as a strategic financial asset, leading to government stockpiling and transfers.

Wartime governments were acutely aware of silver’s importance. In fact, silver became a matter of national security. In 1918, the United States Congress passed the Pittman Act, authorizing the melt of up to 350 million silver U.S. dollars. Ultimately over 270 million silver dollars were melted down, yielding about 209 million ounces of silver bullion for Britain’s war effort.

This extraordinary measure supplied Allied nations (particularly to back Indian rupee coinage for British forces and colonial economies) with silver, while temporarily taking those ounces out of U.S. circulation. It was a clear example of a government favoring strategic and industrial use of silver (and aiding allies) over domestic monetary stockpiles – a form of “silver war” policy. The U.S. later bought silver from domestic mines to replace the melted coins (effectively subsidizing silver miners at $1/oz), illustrating early market interventions to control silver supply and price for strategic ends.

Looking to diversify your portfolio with tangible assets? Jim Cook at Investment Rarities offers expertly curated asset investments with their extremely dedicated team. Discover unique opportunities often overlooked by traditional markets. Visit InvestmentRarities.com Today!

The Military Photography Boom of World War I

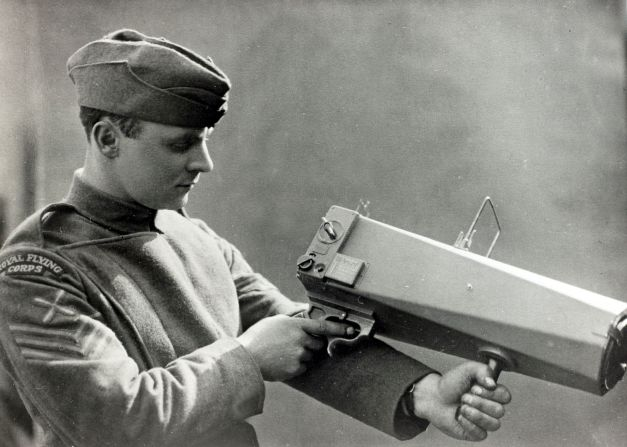

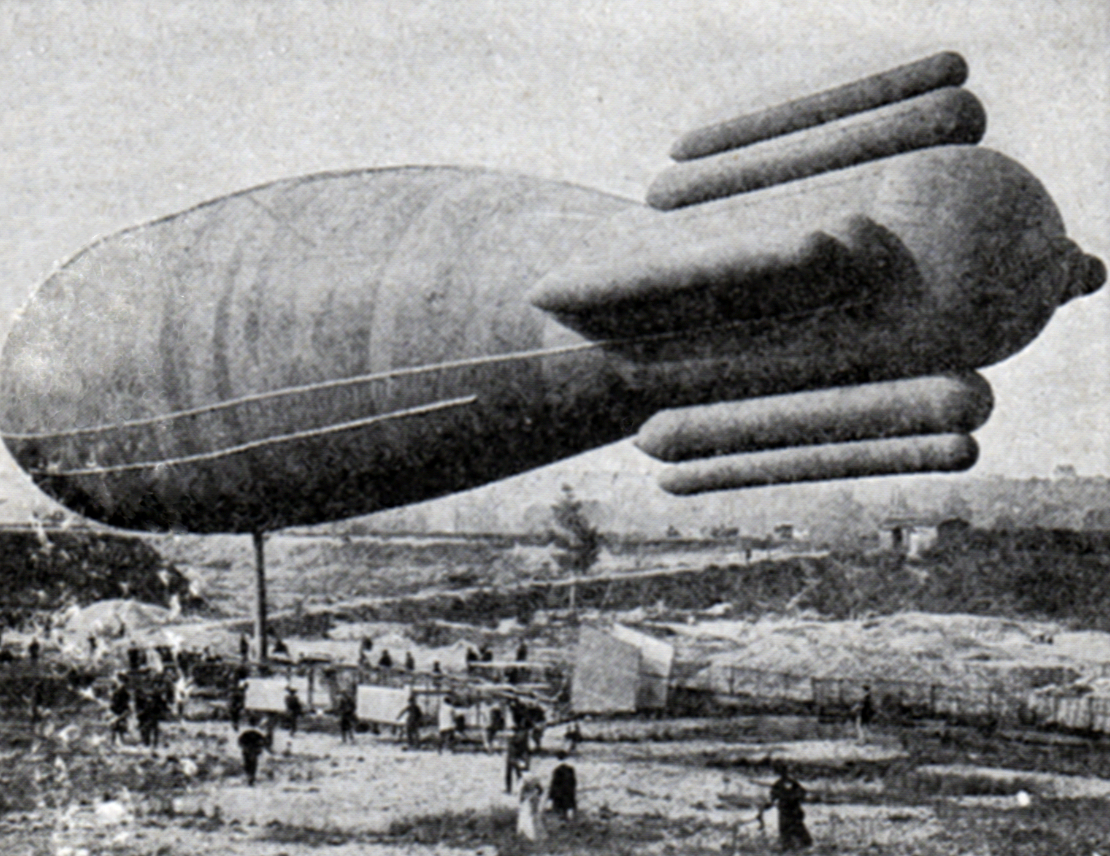

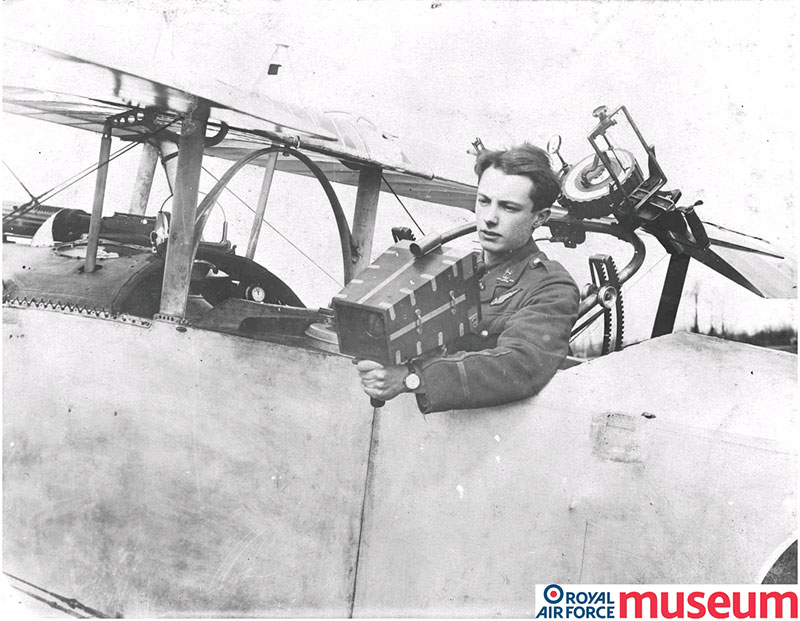

World War I was the first major conflict in which photography was deployed on an industrial scale by all sides. The belligerent nations quickly realized that cameras could be as important as cannons in modern war. Observers and pilots equipped with cameras became the “eyes” of the army, scouting enemy positions from aircraft, balloons, and on foot. This sparked a technological and logistical revolution in photographic reconnaissance – one that devoured enormous quantities of silver in film and photo paper.

Early Preparations: Even before the war, militaries were experimenting with aerial photography for espionage and mapping. Germany was a pioneer – adopting a Görz aerial camera in 1913 – and Austria-Hungary soon followed. In Britain, an Army officer (F.C.V. Laws) had formed an experimental aerial photography unit at Farnborough in 1913. Thus, by the outbreak of war in 1914, several nations had been spying from the sky in a limited fashion, using cameras to gather intelligence a few years before full-scale hostilities began. However, these pre-war efforts were modest – the concept’s real value wasn’t proven until war pressures forced rapid innovation.

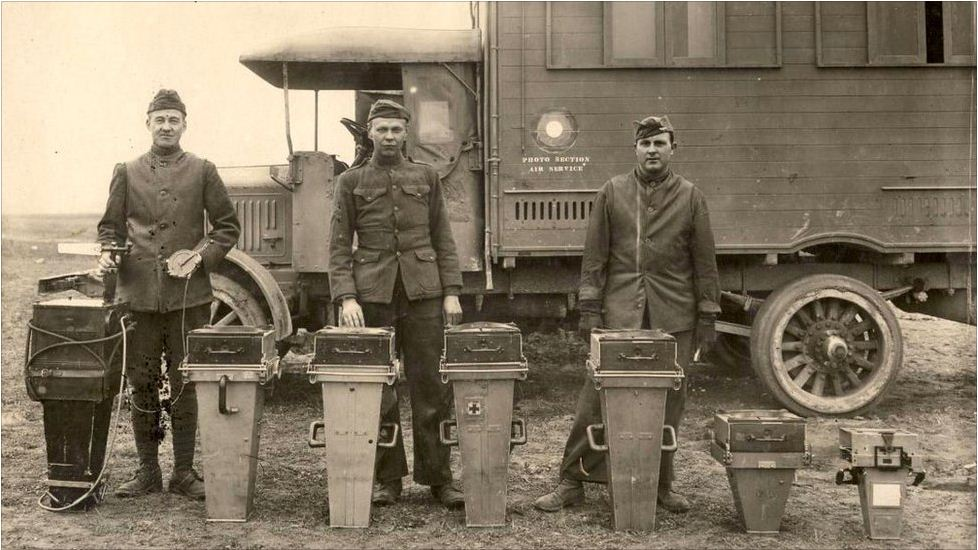

Wartime Expansion: Once WWI began, the use of photography by the military expanded exponentially. France, the world’s aviation leader at the time, immediately equipped aircraft with cameras in 1914, and developed procedures to rush photo prints from plane to command post within hours. The British, initially lagging, soon caught up, standardizing cameras and plate sizes for their Royal Flying Corps. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians likewise integrated cameras into their reconnaissance planes early on. By 1915, what started as ad hoc experimentation had grown into a fully institutionalized military discipline; aerial photography units were established across Western Front armies. Photographic sections also operated in other theaters (Eastern Front, Italian Front, Middle East), though the static trench warfare in France and Belgium proved especially suited to systematic photo reconnaissance.

Scale of Photographic Operations: The scale of military photography in WWI is almost hard to fathom – it was truly industrial in scope. According to archival research in Belgium, “millions of aerial photographs were taken on the Western Front in Belgium and France” over the course of the war. By 1918, at the peak of operations, the German Army alone was producing around 4,000 aerial photos per day to feed its intelligence needs. The British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and French Air Service were equally prolific; one analysis notes that in 1918 the RFC delivered over 5 million aerial images to Allied commanders in that final year of war (including duplicates and prints for analysis). In total, by the war’s end, Allied and Central Powers’ airmen had exposed many millions of negatives and printed far more copies for map-making and targeting. Large photo-mosaic maps were compiled covering entire sectors of the front at scales as detailed as 1:8000 – a testament to how photography became an information weapon as crucial as any artillery barrage.

Every one of those millions of photographs was made using silver. Cameras at the time relied on glass plates or celluloid films coated with silver bromide or silver iodide emulsions, which capture the image. Once developed, each exposed plate held a thin layer of metallic silver forming the photograph, and multiple paper prints could be made (each print likewise containing a few grains of silver in the image). The clearer the photo, the more silver had been reduced to dark metallic particles.

Consider the material implications: an 18×24 cm aerial reconnaissance plate might carry around half a gram of silver in its emulsion. Printing that photo for generals and field commanders might consume another half-gram across several paper copies. Multiplied by millions of exposures, the silver usage becomes enormous. Entire silver mines were, in effect, dedicated to “feeding” the cameras. A rough calculation illustrates this drain: if 10 million military photographs were taken globally during WWI (a plausible order of magnitude given Allied millions plus Central Powers’ output), and each resulted in negatives and prints containing on the order of 0.5–1.0 gram of silver, that would mean 5 to 10 million grams of silver (160,000–320,000 troy ounces) were locked up in war photography. For comparison, 320,000 ounces is about 10 tonnes of silver – effectively removed from monetary circulation and embedded in military intelligence archives, aerial maps, and soldiers’ photo albums.

This was a one-way trip for the metal. Silver used in photographs doesn’t return to bullion markets in any significant amount. In wartime, there was little incentive or ability to recover silver from spent photo-chemicals or old prints – the priority was winning the war, not recycling. Thus, the silver consumed in WWI photography became a permanent “loss” to above-ground supplies. (Decades later, technologies would allow recycling silver from photographic fixer solutions, but during WWI that was not happening at scale.) In essence, photography quietly transformed silver from a mostly circulating asset (coins) into a burnt-out round of ammunition in the information war, expended and effectively gone.

If you appreciate Silver Wars content, please consider giving a donation!

Civilian Photography: A Parallel Silver Drain

Military cameras may have been the hungriest silver consumers during WWI, but civilian photography was not far behind. Despite the war – or in some cases, spurred on by it – amateur and commercial photography blossomed in the 1910s, creating a parallel demand for silver that further strained supplies.

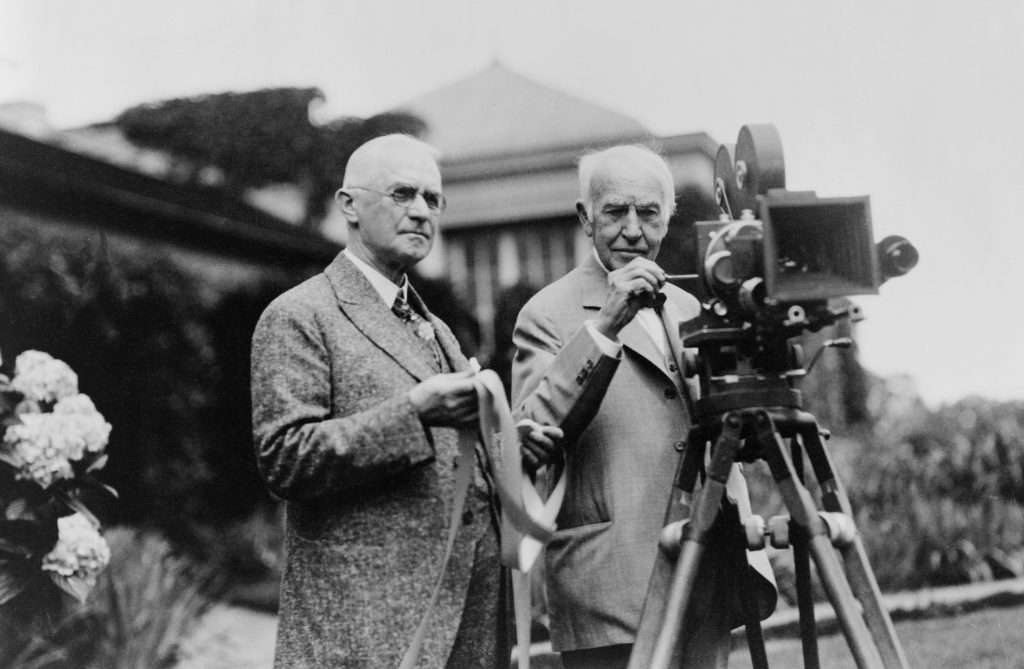

Pre-War Photographic Boom: Thanks to pioneers like George Eastman of Kodak, photography had become accessible to the masses in the years before WWI. The Eastman Kodak Company held a virtual monopoly in film production – by 1895 Kodak was manufacturing 90% of the world’s photographic film. Affordable cameras like the Kodak Brownie (introduced in 1900) put simple box cameras in the hands of millions of people. Each snapshot they took, each negative developed in the family darkroom or by a chemist shop, used a small but cumulative amount of silver. The early 20th century marked the first time in history that large quantities of silver were being consumed for a popular consumer technology rather than for coins or jewelry. In this sense, photography was indeed the trailblazer in transitioning silver into a “useful” metal of industry.

Photography During WWI: The war years saw continued civilian photography, though in combat zones personal cameras were often banned or restricted (soldiers still smuggled them to capture their experiences). On the home front, families exchanged portrait photos with their loved ones at the front, newspapers printed war images (supplied by professional photojournalists), and studios produced millions of photographic postcards – a popular medium of the era – depicting everything from patriotic themes to soldiers’ portraits. All of these uses consumed silver.

It’s worth noting that WWI also coincided with the rise of motion pictures as both entertainment and news. Silver-based photographic film was the medium for movies, and the 1910s saw the film industry take off. War footage and propaganda films were produced by governments (for example, Britain’s 1916 documentary The Battle of the Somme was seen by millions of viewers). Every foot of cinematic film used silver in its emulsion. The nascent Hollywood and European film studios of the 1910s were yet another channel draining silver into images on celluloid.

Medical and Scientific Uses: We should not overlook the medical domain – X-ray photography, invented in 1895, became extremely valuable during WWI for diagnosing fractures and locating shrapnel in wounded soldiers. Pioneers like Marie Curie even set up mobile X-ray units (the “Little Curies”) for French battlefield hospitals. These X-ray plates used silver just like camera film. In addition, surveillance and spy craft extended to photography (spy cameras, darkroom work by intelligence units), again using silver film.

Scale of Civilian Consumption: Precise statistics of silver usage in civilian photography during WWI are scarce, but some indicators give a sense of scale. The U.S. Bureau of Mines in the late 1910s began noting photography as a distinct category of silver consumption, as manufacturers of film and photographic paper bought large amounts of silver nitrate. By one estimate from trade data, photography and photo supplies accounted for a significant portion of industrial silver demand by 1920 – on the order of 5–10% of all silver used. This was unprecedented. Never before had a single industrial application (aside from coinage) taken such a share of the world’s silver.

So, while generals were using aerial photos to plan offensives, ordinary people and businesses were also part of this silent siphoning of silver. When a family snapped a portrait and mailed it to their soldier overseas, or a newspaper printed a half-tone photo (made from a silver-based plate) of the latest battle, they too were incrementally depleting the world’s silver reserves for non-monetary purposes. Photography was becoming entrenched as a daily utility, firmly establishing silver’s role as a dual-purpose metal – both a store of value and a raw material.

Wall Street Silver is under Silver Wars Control.

Now Free from Psy-Ops!

The “Silver War” Between Industry and Money

World War I was a crucible that transformed global economics and industries – and the silver market was no exception. Photography’s huge appetite for silver during the war marked the first large-scale, irreversible transfer of silver from monetary hoards into industrial stockpiles. This had several lasting consequences:

- Perception Shift: After WWI, silver was no longer seen as “just money” or decorative metal; it was clearly a strategic material for modern technology (a trend that would continue with electronics, optics, and, much later, digital photography’s precursors in film).

- Market Dynamics: The competition between monetary use and industrial use of silver began in earnest. Governments had to balance coining silver for currency versus letting it flow to industry. The British and Americans in WWI favored allocating silver to war-related needs (currency for colonies, photographic and electrical uses) even if that meant curbing coinage. This tension foreshadowed later market manipulations – for instance, the post-war British lobbying for a high silver price to restore their colonial currency versus U.S. industrial users lobbying for low prices. We see here the early seeds favoritism to industrial usage and government control of silver markets to ensure strategic supply. The spirit of emergency rule, as later noted by President Eisenhower, extended to critical resources like silver during crises.

- Military Photography’s Silver Appetite: By 1917, aerial reconnaissance, battlefield documentation, and intelligence intercepts relied on film. A single roll of 35 mm motion-picture stock contained roughly 0.5 oz of silver; larger glass-plate negatives used even more. Extrapolating from wartime production:

- Estimate of total photos:

If 200 million oz of silver were melted into photographic emulsions over WW I (≲1914–18 world output), and assuming ≈0.3 oz of silver per average photograph (glass-plate and roll stock blended), that implies on the order of 600 million exposures worldwide.

- U.S. military share:

The U.S. produced roughly 340 million oz during 1914–18 (sum of annual outputs from 1914–18). If 20% of that silver went into military imaging, U.S. forces alone may have shot over 200 million exposures in the war’s years.

World War I’s voracious use of silver in photography represents what we consider the opening chapter of the “Silver Wars” – the ongoing tug-of-war between silver’s role as a precious monetary metal and its indispensability to industry. The war proved that a nation’s ability to see (through reconnaissance and imagery) could be as decisive as its ability to pay, and that required silver in new forms. Military and political leaders of the time, perhaps unknowingly, triggered a paradigm shift: silver’s value would henceforth be measured not just in coins or bars, but in how it could be deployed in technologies that confer strategic advantage.

As we face modern supply crunches in silver for electronics, solar panels, and yes, still photography (albeit digital sensors now dominate, some silver-based photography remains in medical and artistic fields), it’s instructive to recall the WWI experience. Back then, world leaders and mining executives witnessed silver disappearing off the financial ledgers and reappearing as invisible layers in photographs. They learned how easily a surge in industrial need could gut the available supply of silver, and how government controls would be invoked to prioritize critical uses. The audience of today’s policy makers and industry leaders can draw a direct line from those trenches and darkrooms of 1915 to the supply chain dilemmas of 2025.

The history lesson is clear: when silver went to war – whether a shooting war or an industrial boom – its role as money quickly became overshadowed by its role as a strategic resource. Understanding this history helps grasp why silver markets behave the way they do now, with prices sometimes strangely subdued despite high demand: powerful interests and governments have long memories and active hands when it comes to allocating silver where they want it. The silver wars between bullion investors and industrial users have roots over a century old.