The story begins in 1920 with the founding of the Klein & Saks Group in Washington, D.C.—a firm that originally provided general management services and later evolved into a niche consultant for trade associations. Over the decades, Klein & Saks Group (KSG) built a quiet legacy of advising industry organizations on strategy, public affairs, and government relations. By the 1990s, KSG had honed its focus on the mining and metals sector, taking on the behind-the-scenes administration of key industry bodies.

In 1994, Paul W. Bateman joined KSG, bringing with him deep connections in politics and industry. By 1997, Bateman had risen to Present and Chief Executive of the firm. Under his leadership, KSG became the central hub for several high-profile precious metals organizations, effectively outsourcing entire associations to his firm’s management. Through KSG, Bateman would soon be running the daily operations of influential groups in the silver and gold markets.

Paul Bateman’s Ascent from Washington to Metal’s Industry

Paul Bateman’s career is a blend of political pedigree and industry clout. A graduate of Whittier College, Bateman began in national politics in the late 1970s as an aide to former President Richard Nixon. In 1981, he joined President Ronald Reagan’s White House staff, later serving in senior roles at the Commerce and Treasury Departments. By 1989, Bateman was in the George H.W. Bush White House as Deputy Assistant to the President for Management. These roles gave him insider experience in policy and executive management at the highest levels of government.

When administrations changed in the early 1990s, Bateman transitioned to the private sector—specifically to KSG in 1994. His entry into the mining and metals world came quickly. By 1996, Bateman took on the role of Executive Director of the Silver Institute, and a few years later he also became President of the Gold Institute. Holding the top executive titles in both the leading silver and gold trade associations simultaneously was a remarkable consolidation of influence.

Bateman’s network extended beyond metals. In the 2000s, he served as President of the Economic Club of New York (2004-2007), a prestigious forum for business and policy leaders. He also became Chairman of the Reform Institute. This mix of positions – spanning industry, finance, and politics—positioned Bateman as an unusual power broker straddling multiple domains.

The Silver Institute: An Association on Autopilot

The Silver Institute, founded in 1971, is the international trade association for the silver industry. It brings together leading silver mining companies, refiners, bullion dealers, and manufacturers. Ostensibly, the Institute’s mission is to conduct research, publish industry data, and be the voice of the silver sector. However, a peek under the hood reveals that the Silver Institute itself has no direct employees or in-house staff—instead, all its functions are managed by Paul Bateman’s KSG firm.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Bateman served as the Silver Institute’s Executive Director, effectively running the organization via KSG’s management contract. The Institute’s offices for years even shared an address and phone number with KSG, highlighting how inseparable they were. Today, the Silver Institute continues to list an Executive Director (currently Michael DiRienzo), but its IRS filings show zero salary expenses and no direct payroll. All administrative duties, event planning, membership management, and publications are handled by Bateman’s team behind the scenes.

The latest 2023 IRS filings underscore just how dependent the Silver Institute is on Bateman’s network. Once again the Institute reported zero employees, with all core operations outsourced. Of its $1.44 million in revenue, nearly $856,000 (over two-thirds of expenses) went to just two contractors: KSG LLC (Bateman’s firm, $523,000) and Metals Focus Ltd (London-based researchers, $333,000). The World Silver Survey alone accounted for nearly $387,000 of spending, while PR and media costs ran another $344,000. Despite this heavy outsourcing, the Institute still posted a $218,000 surplus, raising its net assets to over half a million dollars. In effect, the Silver Institute functions as a lean pass-through vehicle, funneling member dues into Bateman’s management shop and his chosen data providers, with little direct accountability.

Rise and Fall of the Gold Institute

Bateman’s parallel role in gold was through the now-defunct Gold Institute. Founded in 1976, the Gold Institute was established in Washington, D.C. to promote the gold industry’s interests, publish statistics, and act as the sector’s spokesperson. Like the Silver Institute, it was an association of mining companies, refiners, bullion banks, and equipment suppliers. By the late 1990s, Paul Bateman had become President of the Gold Institute, putting him at the helm of both precious metal institutes at once.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Gold Institute provided industry data and even developed standard benchmarks—for instance, in 1996 it introduced a uniform cost reporting standard for gold mining companies. However, by the early 2000s the Gold Institute’s influence waned. The World Gold Council, founded in 1987 by major gold producers, began to dominate the sector with larger resources and a broader international scope. The Gold Institute quietly ceased operations in the early 2000s, with its function largely absorbed by the World Gold Council and other bodies. Observers noted that the Silver Institute and Gold Institute had been run out of the same offices under Bateman—and when the Gold Institute closed, it left the Silver Institute as the sole surviving precious metals trade group under KSG’s management.

Bateman’s tenure as Gold Institute president thus ended with the dissolution of that organization. Yet, tellingly, he maintained close ties to the gold sector via other avenues – notably through consulting for the World Gold Council (WGC) after the Gold Institute’s demise.

The World Gold Council Connection

The World Gold Council is a much larger entity than the Gold Institute was. Based on London and founded by global gold miners, the WSC focuses on marketing gold, providing investment research, and lobbying on behalf of the gold industry worldwide. While not formally an American trade association, the WGC engages in U.S. policy matters—and here Paul Bateman re-enters the picture.

Klein & Saks Group has represented the World Gold Council in Washington, leveraging Bateman’s D.C. expertise. In 2014, for example, Bateman joined WGC executives in meetings with U.S. regulators. A record of a Commodity Futures Trading Commission meeting on gold market position limits shows Bateman present as a WGC advisor. In such meetings, Bateman helped articulate the gold industry’s position—arguing there was no physical shortage of gold and distinguishing gold from other commodities—to influence regulatory outcomes.

The collaboration indicates that Bateman, via KSG, became an informal Washington lobbyist and strategist for the World Gold Council. It is an interesting dynamic: after shutting down a gold association that he led, Bateman effectively pivoted to working with the bigger global gold body. This provided him continued access to sensitive market information and the ability to help shape narratives about gold’s supply, demand and financial treatment (for instance, under banking regulations like Basel accords).

Data Gatekeepers: GFMS and Metals Focus

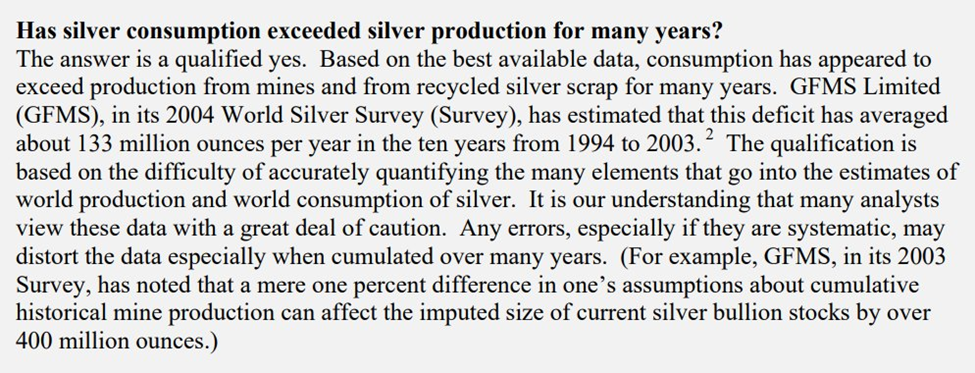

One of the most critical roles of the Silver Institute (and formerly the Gold Institute) is to publish authoritative data on supply, demand, and market trends. Control of this data is power. Under Bateman’s watch, the Silver Institute has been the sponsor of the annual World Silver Survey—considered a definitive report on the silver market—since 1990. For decades, the Institute outsourced the research and writing of this survey to specialist consultancies. Initially, the work was done by CPM Group, then consistently by Gold Fields Mineral Services (GFMS), a London-based metals research firm. GFMS (later acquired by Thomson Reuters) gathered industry data worldwide to produce the Silver Survey and was also long involved in Gold Institute and World Gold Council reports.

Notably, one of GFMS’s early leaders, Philip Klapwijk, interacted with Bateman through industry circles. (Klapwijk later even sat on the board of Bateman’s International Cyanide Management Institute, hinting at close professional ties.) The reliance on GFMS meant the Bateman had a hand in framing the official statistics that market participants rely on. The Silver Institute would release figures on yearly mine production, bullion demand, investment flows, and above-ground stocks—numbers that could sway sentiment about whether silver was in surplus or deficit.

Around the mid-2010s, shift occurred. A new firm, Metals Focus, emerged (staffed by some former GFMS analysts) and began working with industry groups. By 2014-2015, the World Gold Council moved much of its data research to Metals Focus, and shortly thereafter the Silver Institute did as well. Recent editions of the World Silver Survey have been researched and produced by Metals Focus independently, under contract for the Silver Institute. Likewise, the World Gold Council’s quarterly Gold Demand Trends now cite Metals Focus as a key data source alongside their own analysts.

What does this mean? In effect, Paul Bateman’s sphere of influence envelops the data pipeline of precious metals. Through KSG’s management of the Silver Institute, he selects and pays the data providers (now Metals Focus) that generate the numbers the market sees each year. He previously worked closely with GFMS and now coordinates with Metals Focus, ensuring continuity in the narrative. It is telling that Metal Focus proudly notes its production of the Silver Institute’s survey and its deep ties to the World Gold Council—the consulting firm is an insider to both gold and silver establishments.

The Cyanide Code and Other Avenues

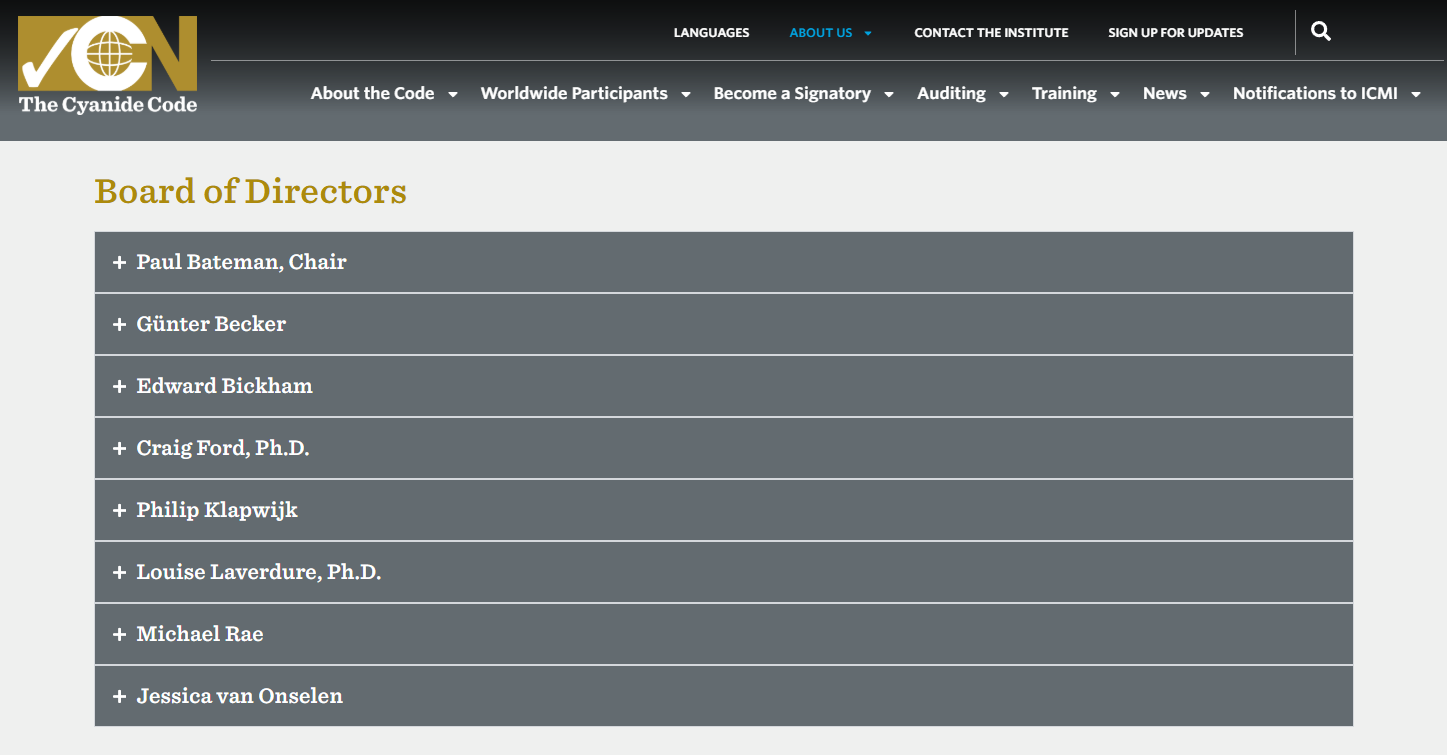

Bateman’s influence in metals goes beyond market data and trade associations. Since 2005, he has chaired the International Cyanide Management Institute (ICMI), which administers the Cyanide Code – a global safety and environmental standard for gold mining (developed with the United Nations). In this role, Bateman convenes major gold mining companies and other stakeholders to oversee responsible cyanide use. It might seem a world apart from price data, but it further cements his connections to all the major gold mining corporations at an executive level.

The Cyanide Code position underscores how Bateman is woven into the fabric of the precious metals industry’s governance and self-regulation. He isn’t just publishing surveys about gold and silver; he’s also guiding best practices and certification programs that large mining firms adhere to. This affords him additional informal leverage – relationships with mining CEOs and sustainability officers, and a seat at the table when industry-wide decisions are made.

At the same time, Bateman’s expanding network of mining executives and policy leaders also intersected with defense contractors and strategic materials planners, hinting that his influence stretched not only across industry governance but into the orbit of the military-industrial complex itself.

The Reform Institute: Political Connections, Defense, and Funding

In parallel to his metals endeavors, Paul Bateman’s stint as Chairman of the Reform Institute adds another intriguing layer. The Reform Institute, founded in the early 2000s, was a centrist think tank advocating for campaign finance reform, national security, and energy policy solutions. Bateman’s involvement (as a Republican-aligned figure working on bipartisan reforms) put him in contact with prominent political and financial patrons.

Notably, the Institute drew funding from philanthropies like the Open Society Institute (connected to George Soros’s Open Society Foundations) and the Tides Foundation, among others. These are liberal-leaning organizations that supported the Reform Institute’s agenda. Yet while it was marketed as a “reform” body, its policy portfolio often bled into areas favored by the military-industrial complex – particularly homeland security, energy independence, and critical materials. Bateman’s leadership came at a time when precious metals were being reframed as strategic defense inputs, not just commodities.

Here the overlap becomes striking: the same Bateman who chaired the Institute was also managing the Silver Institute – an organization historically linked to defense contractors such as Yardney Technical Products, which used silver-zinc batteries in torpedoes and aerospace systems. During the Cold War, the Pentagon even supplied Yardney with silver directly from government stockpiles. Bateman’s consulting firm, KSG, advising metals clients while simultaneously presiding over a think tank that touched national security policy, placed him at a crossroads where mining, finance, and defense converged.

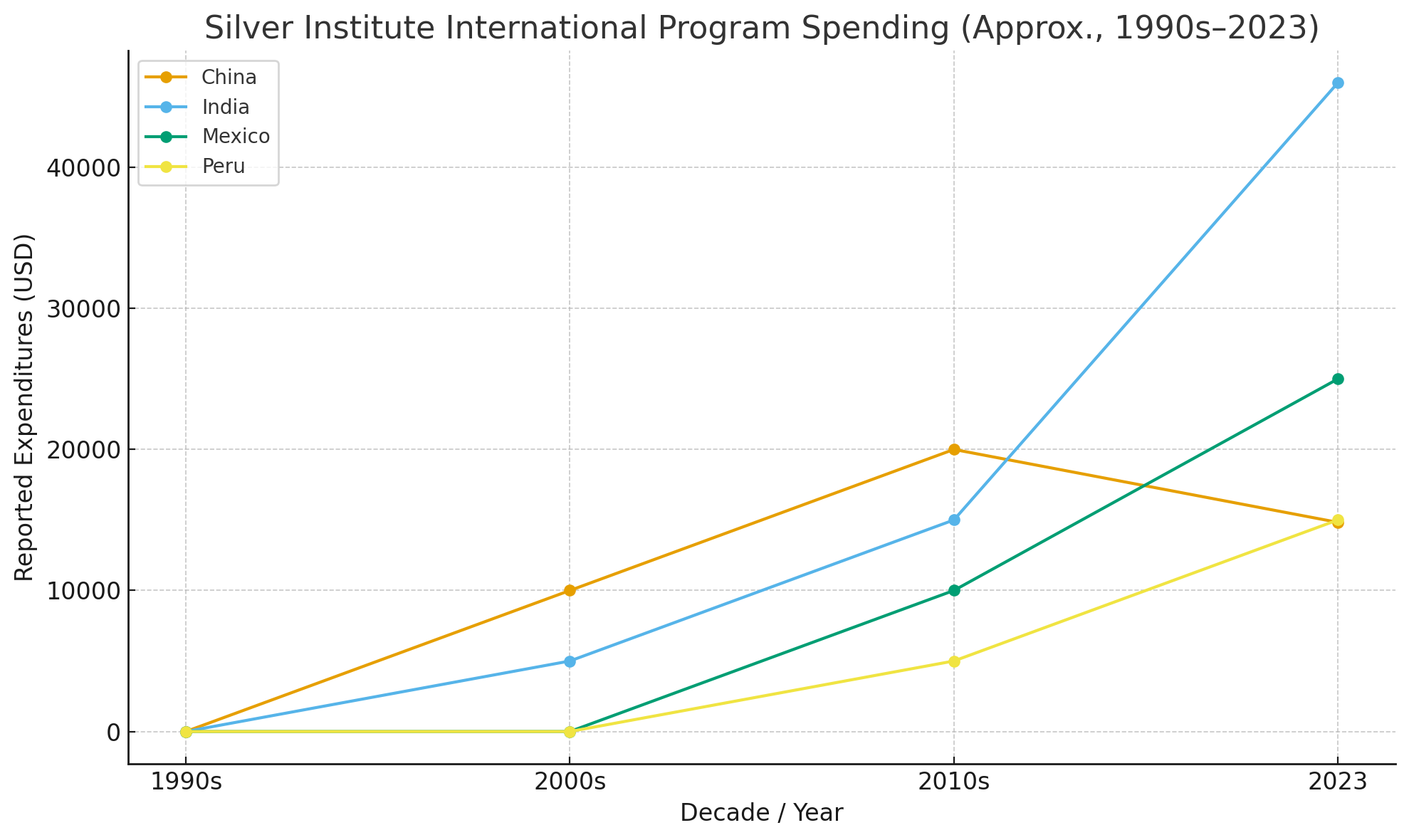

The situation becomes more alarming when one examines the Silver Institute’s IRS 990s from the 2000s through the 2020s. These filings reveal that Institute funds were routinely channeled into China-related programs, including the annual China International Silver Conference (CISC), co-hosted with Chinese state-backed organizations. By the 2010s, the Institute was funding dedicated research on China’s silver market, contracting with firms like Metals Focus to produce reports on Chinese industrial demand and jewelry consumption. And in 2023, the Silver Institute for the first time reported direct overseas expenditures, with nearly $15,000 spent on China-based programs, alongside larger sums in India and other nations.

This means that the very organization once tied to U.S. defense contractors has, under Bateman’s watch, been allocating its limited budget to support silver market development in China—the same country that now dominates global silver refining and industrial demand. At the same time, the Institute has remained structurally dependent on outsourcing to Bateman’s KSG, which receives over $500,000 annually in management fees. In effect, a Washington consultancy with deep ties to both U.S. defense policy and Chinese silver market development is serving as the clearinghouse for the entire industry’s data and narrative.

Critics of the Reform Institute noted that its bipartisan veneer often masked alignment with entrenched defense priorities, channeling funding and intellectual cover for policies that bolstered both Wall Street interests and Pentagon supply chains. But the Silver Institute’s pivot toward China raises even deeper concerns: Has U.S. national security been undermined by allowing a private consultancy to coordinate the industry’s global engagement in a way that strengthens China’s dominance over physical silver supply? With silver embedded in missiles, satellites, advanced communications, and nuclear systems, the implications are stark. The flow of Institute funds and influence into China, orchestrated under Bateman’s oversight, suggests that U.S. strategic autonomy in precious metals has been quietly eroded under the guise of “industry development.”

Controlling the Narrative – and the Market?

Paul Bateman’s unusual career raises a provocative question: Could one man’s quiet control of data and information in the precious metals sector influence the markets themselves?

Consider the elements at his disposal. Through the Silver Institute (and formerly the Gold Institute), Bateman has overseen the publication of supply/demand statistics that most investors, traders, and even government agencies treat as gospel. These reports inform decisions from mine expansions to central bank purchases and ETF flows. If those numbers are presented with a certain slant – for instance, emphasizing a “record surplus” of silver or downplaying a surge in demand – it might temper bullish sentiment and price momentum. Conversely, highlighting a deficit or booming demand could spur buying interest.

Moreover, Bateman’s connections mean he often knows critical information before the public. Mining companies on the Silver Institute board may share production forecasts or sales figures internally. That knowledge – say, that industrial silver demand is surging in solar panels, or that a major mine had unexpected output – could be invaluable. Even without any illegal insider trading, the information asymmetry is notable.

When you layer this with Bateman’s Reform Institute ties to homeland security agendas, the Silver Institute’s historic overlap with defense contractors like Yardney, and now the Institute’s growing financial entanglements with China, the influence looks even more potent. Silver isn’t just a financial asset; it is a strategic defense material embedded in missiles, satellites, torpedoes, and fighter jets. By shaping the data narrative around silver’s supply and demand – while simultaneously nurturing China’s role as the dominant processor and consumer – Bateman sat at a choke point where Wall Street’s bets, Pentagon’s stockpiles, and Beijing’s strategic ambitions intersected. This convergence suggests that precious metals statistics may not only reflect economic conditions but also serve the priorities of the military-industrial complex on both sides of the Pacific.

To be clear, there is no public evidence of falsified data in these surveys. But the interpretation and communication of those numbers is subjective – and subjectivity in this context is power. Bateman’s career shows he understood that framing could serve not only markets and miners, but also policymakers and defense planners who depended on metals availability.

In weaving together the threads – a century-old consulting firm, a Washington insider turned association executive, shuttered and surviving gold and silver institutes, defense-linked contractors, data gatekeepers, political think tanks, and now Chinese partnerships – a picture emerges of Paul Bateman as a man at the center of an opaque web of influence. In an age where data is as valuable as the metals themselves, figures like Bateman remind us that sometimes the most influential players are not the celebrity investors or bullion banks, but the obscure facilitators who curate what the world believes about supply, demand, and value.

A Question of Loyalty – Treason by Information?

When viewed through the lens of U.S. national security, the trajectory of Paul Bateman’s career raises a stark and unsettling question: Has his stewardship of the Silver Institute and its entanglements with China crossed the line from mere influence into something resembling betrayal?

Silver is not just a commodity; it is a critical defense material. It powers missile guidance systems, torpedo batteries, satellites, stealth communications, and nuclear technologies. For decades, the Pentagon relied on domestic stockpiles and U.S.-aligned contractors like Yardney to secure this metal for defense. Yet under Bateman’s direction, the Silver Institute – historically intertwined with U.S. defense supply chains – gradually reoriented its outreach and research toward China, the very nation now recognized as the United States’ foremost strategic rival.

IRS 990s show that Institute funds have been funneled into conferences co-hosted with Chinese state-backed bodies, and even into China-focused research projects. Meanwhile, the Institute’s outsourced management – run by Bateman’s Klein & Saks Group – continues to absorb half a million dollars a year in fees while facilitating these international entanglements. The effect is that a Washington-based consultancy, once embedded in the U.S. defense ecosystem, is now helping to strengthen China’s grasp over global silver markets.

Legally, treason in the United States is narrowly defined in the Constitution: “adhering to [the Nation’s] enemies, giving them aid and comfort.” Whether Bateman’s actions meet that threshold is for courts, not commentators, to decide. But in the broader sense of the word, the optics are damning. By prioritizing international programs that elevate China’s role in silver supply chains, the Silver Institute under Bateman has provided not just “comfort” but strategic leverage to an adversary. When control of critical materials shifts away from the United States and toward a geopolitical rival – and this shift is facilitated by American industry insiders – the line between negligence, profiteering, and treachery begins to blur.

Thus, while Bateman may present himself as a neutral administrator and industry facilitator, the record suggests something far more consequential. By ceding informational power and programmatic focus to China, Bateman has potentially undermined America’s strategic autonomy in silver – a resource essential to both economic strength and military survival.

If treason is, at its core, the betrayal of one’s country’s vital interests to an enemy, then Bateman’s legacy at least warrants that accusation in the court of public opinion.